China has transformed one of the driest, harshest landscapes on Earth — the vast Taklamakan Desert — into a measurable carbon sink through decades of strategic afforestation planting and ecological engineering, according to the latest scientific research and environmental data. In one of the most remarkable ecological turnarounds of recent history, vegetation now absorbs more carbon dioxide (CO₂) around the desert’s edges than the desert emits, redefining what was once called a “biological void.”

This breakthrough is significant because combating climate change now demands active carbon removal in addition to cutting emissions. That’s why this development matters now and deserves global attention: transforming a desert — historically inhospitable to life — into a carbon-absorbing landscape shows what strategic, long-term nature restoration can achieve.

The Unlikely Story of the Taklamakan Desert’s Transformation

The Taklamakan Desert in northwest China — larger than Montana and nearly half the size of Germany — has long been one of the world’s most arid places, blanketed by shifting sand and extreme lack of vegetation. Until recently, scientists considered it a “biological void” that contributed little to carbon cycles because plants were virtually nonexistent.

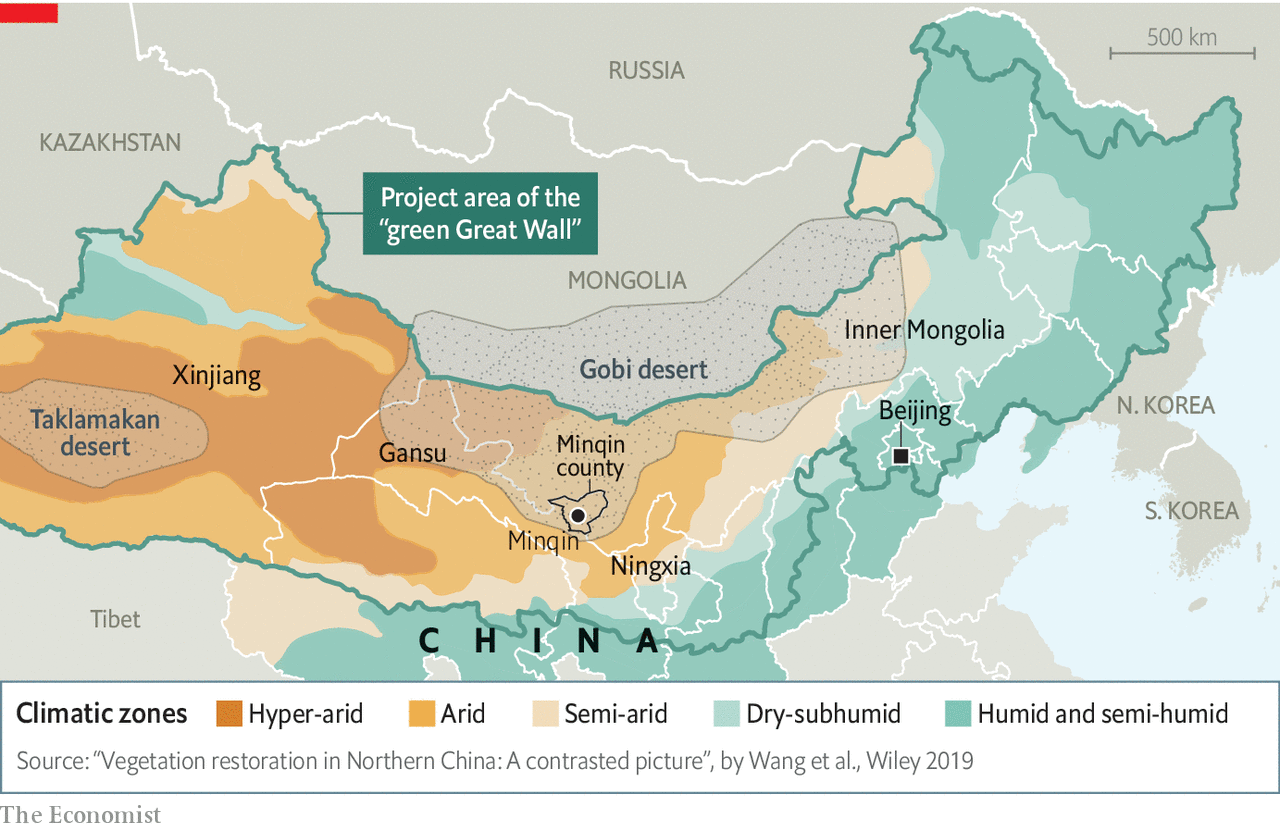

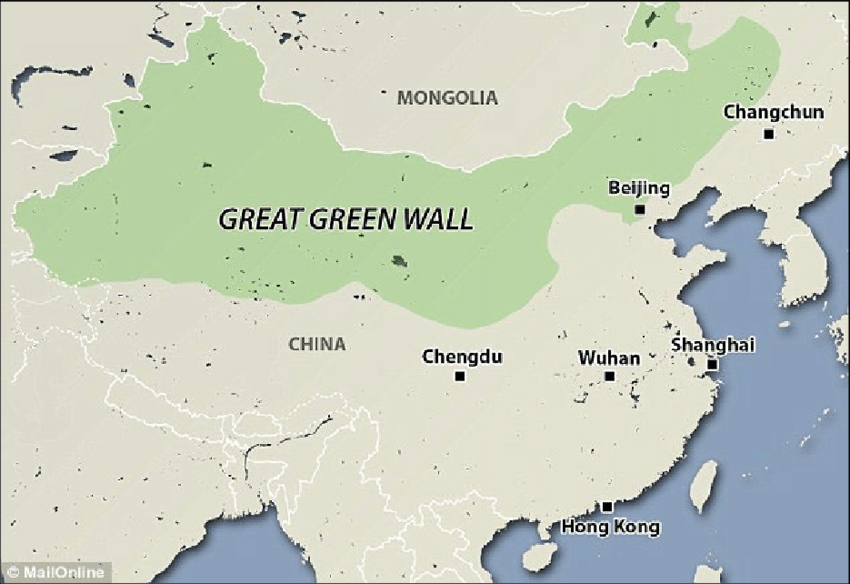

However, starting in 1978, China launched the Three-North Shelterbelt Program, also known as the Great Green Wall, intending to slow desertification by encircling major deserts with planted forests. Over the decades, this initiative expanded to become one of the largest ecological engineering projects ever attempted — planting over 66 billion trees around the edges of the Taklamakan and other deserts.

Recent data released from long-term satellite analysis and scientific modeling shows that vegetation planted along the desert’s rim has gradually stabilized soil, increased plant cover, and improved carbon uptake processes — meaning the perimeter now absorbs more CO₂ than it releases. This marks a real shift from desert to carbon sink.

How Trees and Shrubs Are Making the Desert Greener

The afforestation efforts focused not only on traditional trees but also on planting hardy shrubs and desert-adapted vegetation capable of surviving arid conditions. Researchers used satellite data and carbon tracking tools to monitor trends over 25 years, noting consistent increases in photosynthesis and vegetation greenness.

During seasonal rainfall, vegetation growth accelerates substantially, helping capture CO₂ through photosynthesis. While rainfall in the desert remains limited, even small increases in moisture during wet months are enough to activate plant growth around the desert margin. This effect, combined with decades of tree planting, has changed the region’s net carbon balance.

This transformation did not happen overnight — it required long-term planning, sustained effort, and scientific monitoring — proving that large desert ecosystems can play a meaningful role in reducing atmospheric carbon.

Why This Breakthrough Matters for Climate Solutions

Few climate strategies have shown such measurable, real-world carbon removal on a landscape scale. Although the Taklamakan sink currently sequesters only a fraction of global emissions, it offers a model for other dry regions facing desertification and climate stress.

Afforestation in extreme environments is controversial among experts because tree planting must be matched carefully with water availability and long-term ecosystem sustainability. Too many tree failures or monoculture planting can backfire, as lessons from other projects have shown.

Nevertheless, the Taklamakan case shows that with the right species selection, scientific guidance, and commitment, even hyper-arid zones can contribute materially to climate mitigation. It expands how researchers and policymakers think about carbon sinks worldwide and encourages innovation in nature-based climate solutions.

Ongoing Challenges and the Path Ahead

Although the Taklamakan’s fringe vegetation now helps absorb carbon, scientists caution that long-term success depends on water management, ecosystem diversity, and climate conditions. Sahara-like climates naturally resist vegetation growth, and without careful planning, the gains could falter.

Moreover, while the desert’s carbon sink contribution is noteworthy, it remains small compared to the global challenge of cutting billions of tons of CO₂ emissions each year. Tree planting alone will not solve climate change — it must be paired with deep emissions cuts, renewable energy adoption, and innovative carbon removal technologies.

Still, the Taklamakan achievement represents proof of concept: human intervention at scale can alter ecosystems once deemed hopeless. And as climate impacts accelerate, experiments like these will be increasingly valuable on a global scale.

China’s successful transformation of the Taklamakan Desert from barren sandscape to functioning carbon sink shows that, with patience and science-based environmental planning, landscapes once written off as ecological wastelands can play a positive role in fighting climate change.

Subscribe to trusted news sites like USnewsSphere.com for continuous updates.