Western Babies Missing Key Gut Bacteria Linked to Lifelong Health Risks, Scientists Warn

Missing Baby Microbiome in Western Infants and Its Global Health Implications — New research reveals that many babies born in Western nations are missing a vital gut microbe that most infants in Africa, South Asia, and other regions naturally carry — a discovery with far-reaching implications for immune development and lifelong health. Babies start with nearly sterile guts at birth, and the first microbes they acquire help shape digestion, immune defenses, and disease risk; yet modern lifestyles and industrialized environments appear to be reshaping this invisible ecosystem right from the first weeks of life. This matters now because rising rates of autoimmune and allergic diseases in Western countries may be connected to weakened early-life microbial exposure, prompting scientists to rethink how infant probiotics are developed and deployed.

How Western Babies’ Microbiomes Differ from the Global Norm

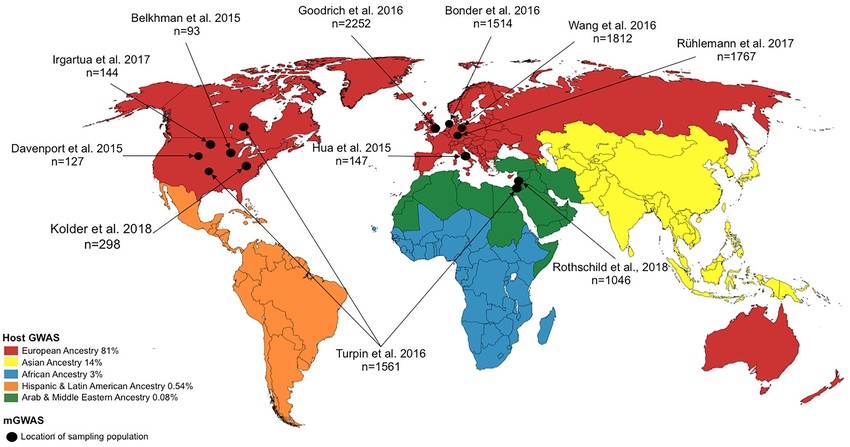

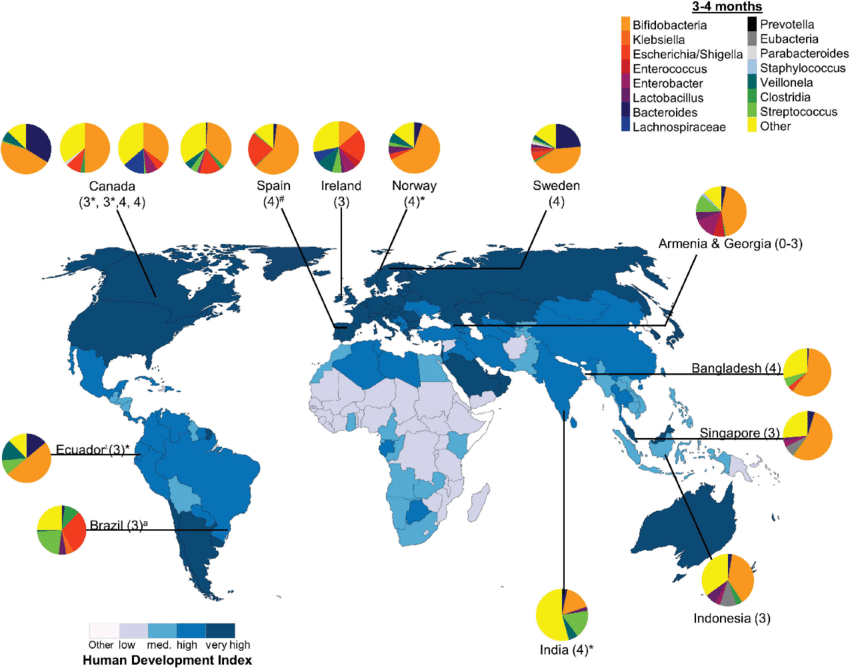

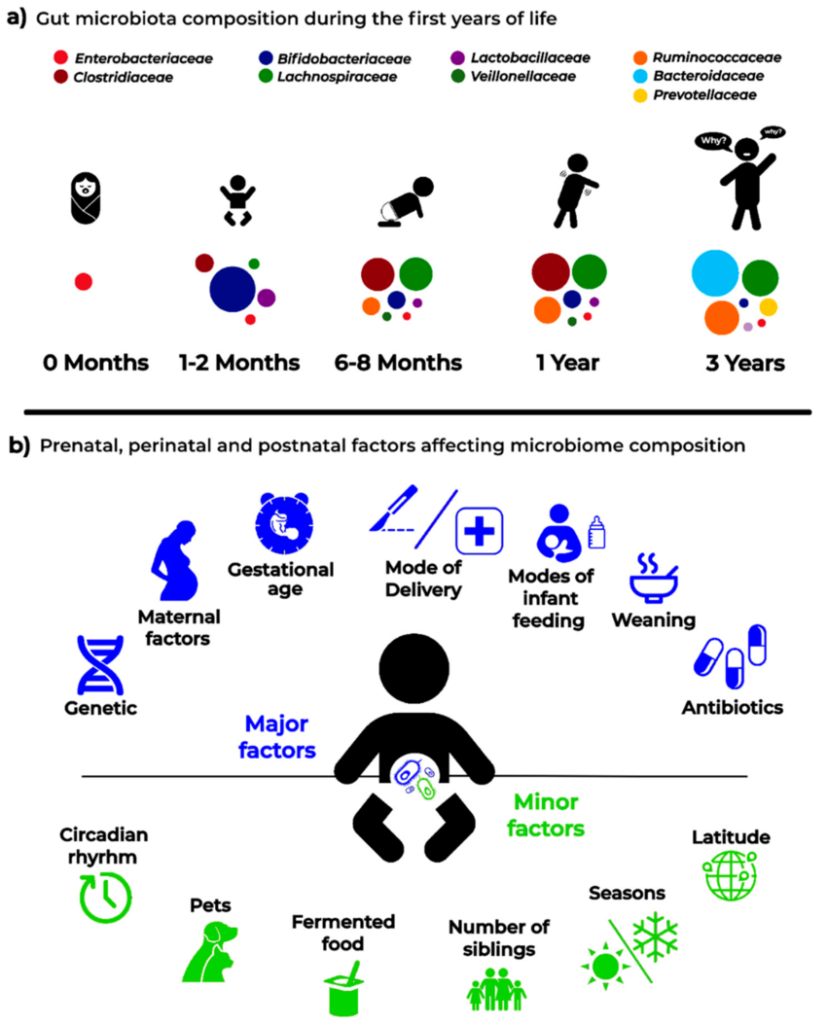

When experts mapped thousands of infant gut bacterial genomes from 48 countries, they found one striking pattern: a species of bacteria called Bifidobacterium infantis — known to efficiently digest breast milk and train the immune system — is common in infants in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia but nearly absent in babies from the UK, Europe, and North America.

Scientists believe this “missing microbe” doesn’t thrive in Western environments due to multiple factors: antibiotic exposure, shorter breastfeeding durations, highly processed diets, lower exposure to soil and environmental microbes, and overly sterile living conditions. These shifts can change how a baby’s gut ecosystem assembles, potentially affecting lifelong health outcomes.

Traditionally, B. infantis and related bacteria help break down complex breast-milk sugars that other microbes can’t, giving them a competitive edge and helping establish a diverse, balanced gut microbiome in early life. This balanced ecosystem teaches the immune system to distinguish between friend and foe and reduces inflammation.

Why Infant Microbiomes Matter for Lifelong Health

Infant gut microbes are not just passive passengers — they play an active role in developing a baby’s immune system, metabolic health, and even brain-gut communication. Early research from Stanford Medicine and other groups showed that as nations industrialize, bacteria like B. infantis — which digest breast milk sugars — decline sharply, possibly reducing some of breast milk’s protective effects on gut immunity and inflammation control.

This matters because the early microbiome impacts:

- Immune training: Helping the developing immune system learn what to attack and what to tolerate.

- Digestion and nutrient absorption: Assisting with breaking down nutrients that infants can’t digest on their own.

- Disease risk: Some patterns of microbial imbalance have been linked to increased allergy, asthma, and autoimmune conditions later in life.

Researchers have also found that changes in hygiene brought on by global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic may have temporarily reduced microbial diversity in infant guts, further highlighting how environmental and social factors shape these early ecosystems.

Why Western Microbiomes Are “Missing” Natural Strains

Another surprising finding from the global microbiome atlas is that most commercial infant probiotic strains trace back to only a few historical bacterial lineages — and these are not the same strains found in infants from non-Western regions today.

This suggests that many over-the-counter probiotics may not be ideally matched to the microbes babies need in the modern era, especially in Western countries where microbial diversity is already reduced. Tailoring probiotics to match regional dietary patterns and the microbes naturally adapted to a given environment may yield more effective outcomes than a one-size-fits-all approach.

For example, strains from West Africa identified in the atlas have genes linked to breaking down traditional staple foods like fonio millet — features unlikely to be present in commercial strains developed in Europe or the US.

How Birth Practices and Diet Shape Infant Microbiomes

Microbiome development begins at birth, and several factors influence which bacteria succeed in colonizing the gut. Research shows that:

- Vaginal birth tends to transfer more diverse maternal microbes compared with cesarean section delivery.

- Breastfeeding promotes Bifidobacteria dominance due to specific sugars in human milk.

- Formula feeding and antibiotics may reduce beneficial bacteria or slow their establishment.

These early influences can create cascading effects on immune training and metabolic programming in later childhood and adulthood.

What This Means for Future Infant Health and Probiotic Solutions

The discovery that many Western infants lack a foundational gut microbe doesn’t just deepen our understanding of global microbiome variation — it calls for a rethink of health strategies that support early-life microbial diversity.

Experts now suggest:

- Developing region-specific probiotic strains that reflect the microbes babies naturally developed with for millennia.

- Rethinking infant nutrition and early life practices to support microbiome establishment.

- Expanding global microbiome research to include underrepresented regions for more complete insights into human microbial ecology.

By focusing on natural microbial diversity rather than narrow commercial products, scientists hope to help infants worldwide develop more robust gut ecosystems, with benefits that last a lifetime.

Subscribe to trusted news sites like USnewsSphere.com for continuous updates.